Conservation versus local livelihoods? Sustainable development challenges in Madagascar

In many people’s imagination, the island of Madagascar is synonymous with beautiful rainforests and exotic animals found nowhere else. Often absent from this foreign view, however, are the human inhabitants of the island – the Malagasy people. Largely reliant on small-scale agriculture, access to land is crucial for their survival.

In many people’s imagination, the island of Madagascar is synonymous with beautiful rainforests and exotic animals found nowhere else. Often absent from this foreign view, however, are the human inhabitants of the island – the Malagasy people. Largely reliant on small-scale agriculture, access to land is crucial for their survival. With few agricultural inputs or technology available, shifting cultivation is a well-adapted, rational land use practised by many Malagasy to grow staple crops. But as various factors – demographic, market-based, etc. – put the whole land use system under pressure, shifting cultivators are forced to expand their farming into remaining forests. This causes conflict with those who want to conserve Madagascar’s forests and extraordinary biodiversity as a global good.

Protected areas and paddy rice support

To prevent loss of the last remaining large humid forests along the northeast coast, Western conservation organizations successfully lobbied Madagascar’s government to establish the protected areas of Masoala, in 1995, and Makira, in 2005. In addition, conservation and development organizations launched projects to support intensification of smallholder agriculture – particularly irrigated (paddy) rice – in the areas near protected zones. They hoped this would make local land users quit shifting cultivation, thereby reducing deforestation.

CDE’s research shows that irrigated-rice production increased by 33% (by surface area) in northeast Madagascar between 1995 and 2011. Critically, however, the increase in paddy rice did not reduce shifting cultivation in the region. Overall, shifting cultivation remains present to some extent across more than 80% of the landscapes in the study region (by surface area). Further, over 80% of approximately 1,200 households interviewed in 45 villages said they continue to rely on shifting cultivation to meet at least part of their subsistence rice needs.

Diverse landscapes and benefits

CDE’s research also sought to shed light on how different people benefit from land in northeast Madagascar. One key question is whether different landscape types can be characterized according to different bundles of “ecosystem services” linked to land use. The analysis shows that although the overall composition of ecosystem services linked to land uses is similar across landscape types, the perceived importance of different ecosystem services varies widely from one household to another.

Land uses and ecosystem services in mixed paddy landscapes

Move your mouse pointer over the graph. Placing the pointer over any node reveals the links between landscape types, land uses, and ecosystem services. Hovering over any link will show you the percentage of people who perceive a given ecosystem service as important in the respective landscape / land use type.

Land uses in mixed shifting landscapes

Land uses in paddy landscapes

Visualization by Christoph Bader modified based on Cale Tilford’s code.

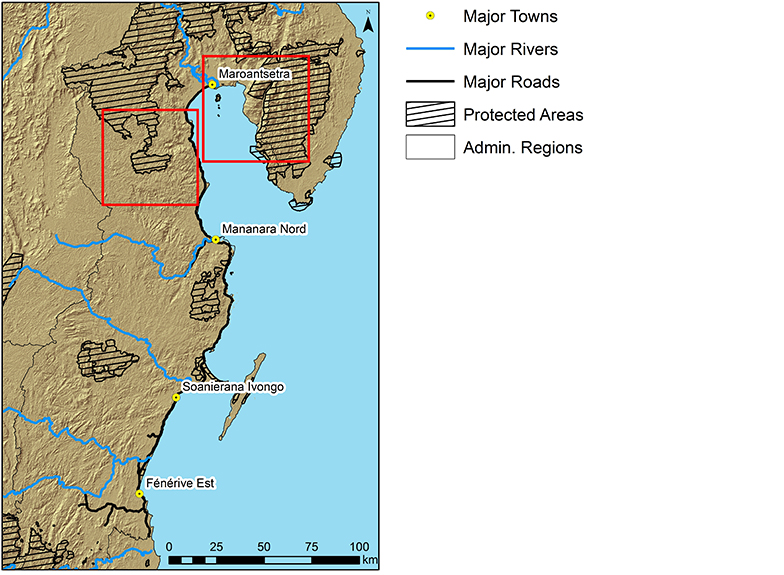

Deforestation and agricultural development on Madagascar’s northeast coast

Notably, while deforestation decreased in the conservation areas, it increased in the rest of the landscape. With the large forest massifs enclosed in protected areas, local land users were forced to target remaining forest fragments to expand their agricultural fields. Altogether, another 11% of the region’s forests disappeared, mostly outside protected zones. And the deforestation rate accelerated at the end of the 16-year period. The threatened forest fragments may be crucial to the ecological integrity of the landscape, providing habitats for different species and beneficial microclimates. If this trend continues, landscapes in our study region will probably become much more homogeneous.

The map on the left show the locations of the two maps below in the southern part of today’s Makira Natural Park and in the Masoala National Park. The two zoomed maps show how land uses have changed between 1995 and 2011.

Visualization by Christoph Bader

Read the Policy Brief online:

Zaehringer JG, Ramamonjisoa B, Messerli P, Lannen A. 2018. Conservation Versus Local Livelihoods? Development Challenges in Northeast Madagascar. CDE Policy Brief, No. 12. Bern, Switzerland: CDE.

Suggested further readings:

-

- Amin A, Zaehringer JG, Schwilch G, and Koné I. 2015. People, protected areas and ecosystem services: A qualitative and quantitative analysis of local people’s perception and preferences in Côte d’Ivoire. Natural Resources Forum 39(2):97–109. doi:10.1111/1477-8947.12069. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1477-8947.12069/full

- Zaehringer JG, Schwilch G, Andriamihaja OR, Ramamonjisoa B, Messerli P. 2017. Remote sensing combined with social-ecological data: The importance of diverse land uses for ecosystem service provision in north-eastern Madagascar. Ecosystem Services 25:140–152. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.04.004. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212041617302619

- Zaehringer JG, Hett C, Ramamonjisoa B, Messerli P. 2016. Beyond deforestation monitoring in conservation hotspots: Analysing landscape mosaic dynamics in north-eastern Madagascar. Applied Geography 68:9–19. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2015.12.009. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0143622815300357

- Zaehringer JG, Eckert S, Messerli P. 2015. Revealing regional deforestation dynamics in north-eastern Madagascar: Insights from multi-temporal land cover change analysis. Land 4(2):454–474. doi:10.3390/land4020454. http://www.mdpi.com/2073-445X/4/2/454/htm

I read with great interest this policy brief. Particularly the 4th key message: “policymakers should support … improved income opportunities …” is an important conclusion. My organization, Swisscontact, implements some projects which intend to provide such opportunities, especially in Indonesia, where similar problems persist, aggravated by large commercial plantations for palm-oil and extracting industries. Our responses focus on increase the productivity of cash-crops for small holders (cocoa, aromatic plants) and promotion of sustainable tourism (see examples on our website). The former initiatives pretend to establish a buffer zone adjacent to forests, while for sustainable tourism protected nature is an important asset at the same time providing an alternative income. GIZ had once a project in Ecuador where they tried to arbitrate the interests of oil companies, indigenous communities and tourism operators. Such arbitration processes can be a powerful instrument to balance the different interests, finally to the benefit of the natural eco-system.

Thank you very much for your interest in our policy brief and its key messages. While cash crops are an important income source for land users in north-eastern Madagascar already, many challenges with respect to productivity, quality, and market access persist. Income opportunities could be improved takling these issues. As you say, negotiation processes between different actors are necessary to move towards a more sustainable land use in this region. Through our “Managing telecoupled landscapes” project we are establishing stakeholder platforms and enable social learning.